Forced disappearance in the Brazilian Western Amazon

The disappearance of journalist Dom Philips and indigenist Bruno Pereira, in Vale do Javari, in Amazonas, once again highlights the high levels of violence in the Brazilian Western Amazon, a region comprised by the states of Rondônia, Acre, Amazonas and Roraima.

The case has many similarities with another episode that took place in 2017, in Canutama, south of Amazonas, on the border with the state of Rondônia.

In that episode, a former ICMBIO brigadier, Flávio de Lima de Souza, and two peasants, Marinalva Silva de Souza, and Jairo Feitosa, disappeared in an area of federal land, a region of agrarian conflicts.

In the case of Flávio, Marinalva and Jairo’s disappearance, it took months for the families to obtain a response from the authorities about the official opening of an investigation.

Forced disappearances do not always occur in inhospitable regions, with difficult access. This was the case with the disappearance of Ruan Lucas Hildebrandt, who in 2016 disappeared after being attacked by security guards at a farm in Cujubim, Rondônia, along with 4 other friends, during a reintegration authorized by justice. The body of Alysson Henrique Lopes, who was unable to escape, was found hours later, charred, inside a car.

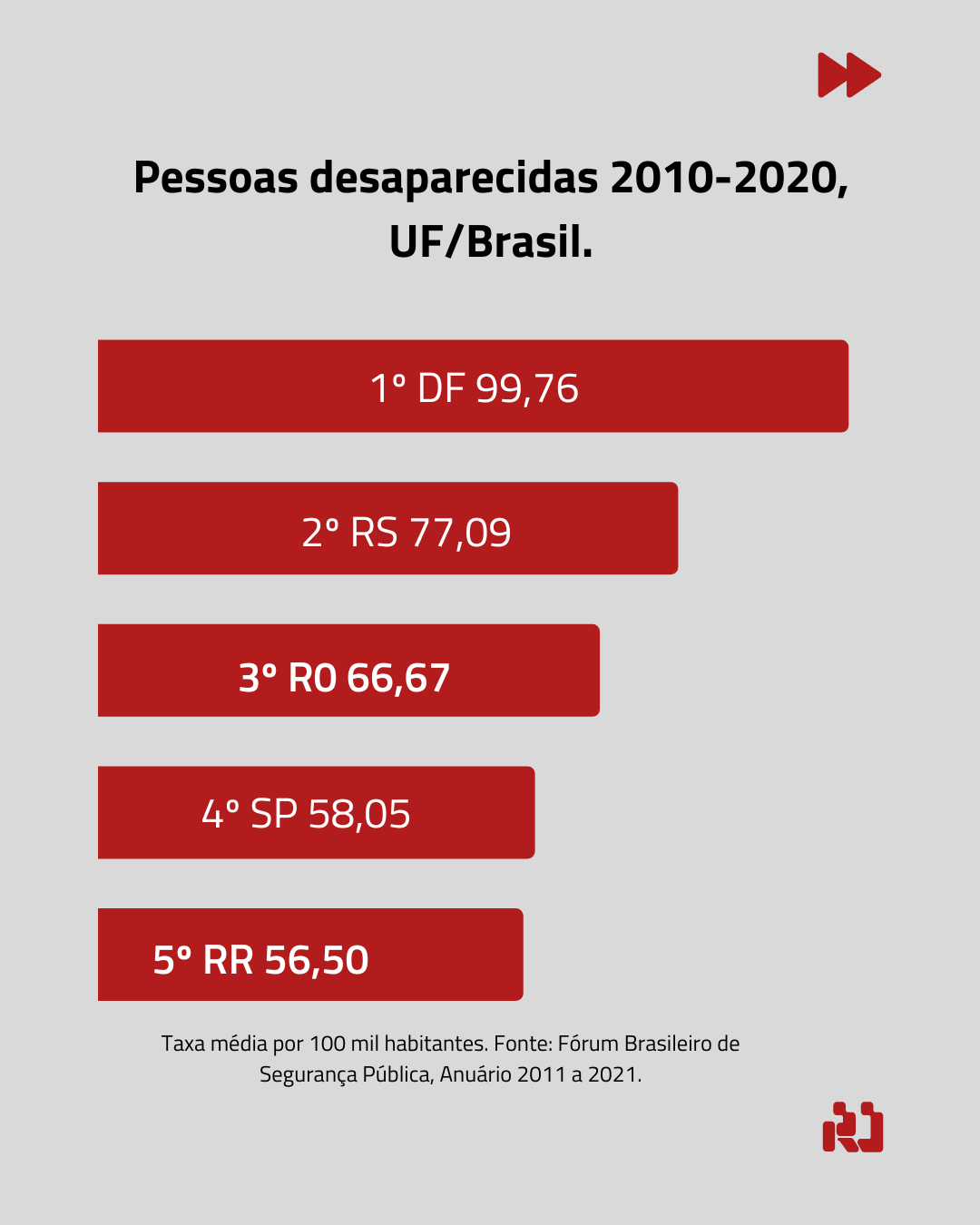

In this western portion of the Amazon, data from the Brazilian Public Security Forum show that the state of Rondônia is the champion in the disappearance of people, boasting the 3rd highest average in the country in the last 10 years.

In 2020, Rondônia was only behind the Federal District, with 60 disappearances per 100,000 inhabitants. In 2019 and 2020 alone, more than 2300 people disappeared in Rondônia.

Adding RO, AC, RR and AM, in 2019 and 2020 alone, more than 4550 people disappeared.

In the same period, the 4 states reported that only 240 people were found – just over 5% of that total*.

The disappearance of Bruno and Dom reveals yet another face of this enormous problem: the relationship between the disappearances and the very particular identity of the Amazonian conflicts.

These conflicts are caused by the ongoing threat to traditional communities and indigenous peoples.

They are further exacerbated by the advance of land grabbing, illegal logging, illegal mining, and increased demand for cocaine transport routes from Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia.

Large regions, previously isolated and well protected, are becoming new targets for all kinds of illegalism.

This movement has been further strengthened by the weakening of the means of control and protection of the environment caused by the federal government in recent years.

In 2021, IBAMA used only 41% of the budget for environmental inspection and other important bodies, such as ICMBIO and FUNAI, have systematically lost personnel and revenue.

In April 2020, FUNAI published a normative instruction (n. 9) that makes it easier to sell land that is in dispute with indigenous people, whose demarcation processes are not finalized or are awaiting completion.

This was just another major normative step taken in the direction of destroying the already fragile mechanisms of protection for indigenous territories. FUNAI currently has more than 2330 vacant positions, against only 1717 active servants.

The Javari Valley is the region with the highest concentration of isolated peoples or peoples in voluntary isolation on the planet.

In the Brazilian Amazon, FUNAI records point to 114 isolated peoples or peoples in voluntary isolation, as the indigenous people who live far from other groups, indigenous or not, are called. In Vale do Javari alone, there would be 16 peoples (according to the Socio-Environmental Institute, this number can reach 26).

The advancement of wood and fishing extractive groups and the multiplication of illegal mining areas puts each of these peoples at risk of extinction.

This process of predatory and indiscriminate exploitation of the natural wealth of the Amazon does not occur without the State’s participation being decisive: the deliberate destruction of the means of protection and defense works not only as a sign that

As the pressure for occupation and exploitation of untouched lands and vegetation increases, the systematic policy of destroying the region’s defense mechanisms is a clear sign that the curve of illegalism will continue to grow, without major obstacles.

Behind the disappearance of Bruno and Dom there are many indications that violence in the Western Amazon will continue to increase.

*The number of people found in 2019 and 2020 does not necessarily refer to the people who disappeared in 2019 and 2020. The states consulted did not inform how this data is produced. Data on disappearances are in the Yearbook of the Brazilian Public Security Forum, from 2011 to 2021.